The Lower East Side has everything that makes a neighborhood maddeningly, quintessentially Manhattan—streets at inexplicable angles, buildings from every period, and borders that, depending on if you’re 25, 55, or 105, shift 5 or 15 blocks. Here, though, is what most can agree is the indisputable core of the Lower East Side.

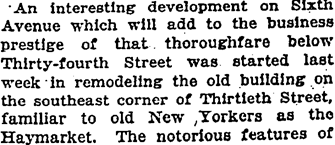

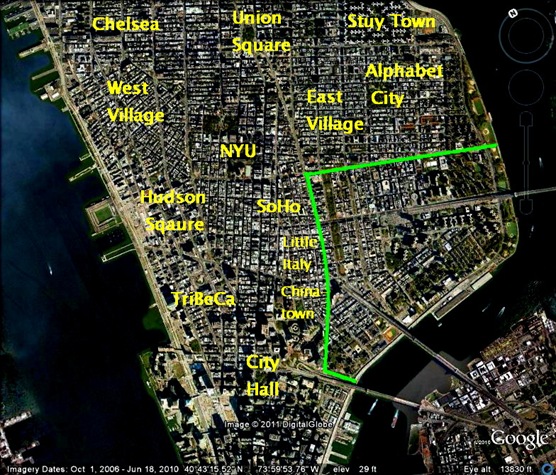

Across nearly every running foot of the green line above is a neighborhood that can be persuasively argued to be part of the Lower East Side—Alphabet City, the East Village, Little Italy, “traditional” Chinatown, not to mention ghost neighborhoods like Kleindeutschland and Five Points, among others. The boundaries of the area are: Houston Street to the north, the Bowery to the west, and Chatham Square and Catherine Street to the south (actually, the southern border runs along the Brooklyn Bridge anchorage, across the Al Smith Houses from Catherine Street, Robert F. Wagner Sr. Place—but who knew there was such a street).

Just to lay it all on the table, purists will insist that everything in the blue boundary is the Lower East Side. It’s no use arguing with these people.

First, let’s look at a century of advancement in transportation and how the Lower East Side has—literally—been pushed off to the side. The Bowery (the green curved line above) was once the main road in and out of town when impassable marshland extended across TriBeCa from Broadway to the Hudson River. (To read more about that, go to: The Truth about Broadway—and Manhattan’s Water Border). Today, however, it’s far easier to navigate the west side of lower Manhattan than the east side. You’ve probably been to Chelsea, the West Village and TriBeCa far more often than the Lower East Side—here’s why.

The next two images are basically the same, showing the main uptown-downtown avenues, the second map labels them. An arrowhead at both ends of a yellow line indicates a two-way street; one arrowhead is a one-way street. Where two arrowheads come face-to-face indicates “no through traffic.” What’s amazing is that the West Village is notorious for its crazy street patterns, and car traffic cuts through easily. It’s a different story on the east side.

The west side avenues 6, 7, 8 and 9 feed directly into Church, Varick, Hudson and Greenwich Streets—drivers would actually have to look at the street signs to realize they’re on a different street. On the east side, though, you have to make a half dozen turns to make your way into lower Manhattan (or travel uptown). As well, avenues 11 and 12 feed into the the West Side Highway (which becomes West Street below 14th Street). The FDR Drive is its own road, with three exits in the LES: Houston, Grand, and South Street.

It’s the same for the subways. It looks as if there are plenty of subway lines running through the LES below…

But most are just passing through. Here are the actual subway stops.

Most people know there’s much public housing in the area, but blocks of housing developments actually form a virtual wall around the district (of course, plenty of people live in that “wall”).

And lastly, there are the Williamsburg and Manhattan Bridges that have turned so much of the Lower East Side into a landing pad. It’s incredible to think about, but the bridge approaches weren’t even planned until the bridges were near completion. The Williamsburg Bridge opened in 1903, and helped (along with the elevated trains that led up to Harlem) de-populate a severely over-populated Lower East Side, especially for the Orthodox Jews who could walk over the bridge on Sabbath (and Williamsburg has a large Jewish population as a result today). The Manhattan Bridge opened in 1909.

The Lower East Side is much more extensive than the 6-8 block cluster of clubs and cafes located within a short walk of the subway stops. A five minute walk from the heart of the district towards the shore leads to a neighborhood that has a completely different look and feel. Between the clubby noir Lower East Side of tenements and the wall of massive apartment buildings along the shore, are a few one-and-two-story high “main street” strips of pharmacies, delis, beauty saloons and locksmiths. It actually feels like outlying areas of Brooklyn and Queens.

This disjointed “indisputable core” of the LES is the combination of two fossil farms that can be seen clearly in the street patterns today: the Delancey and Rutgers estates. (Technically, it's just Lancey, since the name is de Lancey, but Lancey alone looks weird). Both estates bordered the Bowery, and each had a main road: Grand Street on the Delancey estate, and Love Lane on the Rutgers estate.

Below is the Montresor map of 1766. According to Stokes, there are many inaccuracies on this map, it was done for the British after the Stamp Act Riots of 1765, and in secret, so only certain features were important—like roads, not farms. I’m using it to show Grand Street, which the British called the “Road to Crown Point,” which was what the British called Corlears Hook, the land feature that gives Manhattan its distinctive bulge. That road, which would be named Grand Street a few years later, bisected the Delancey estate and traversed one of the city’s highest hills, Mount Pitt (aka Jones Hill). Another road, Love Lane ran across the northern stretch of the Rutgers farm. The next map zooms in on the area.

Stokes, Vol 1, p. 339

Stokes, Vol 1, p. 339The Road to Crown Point (Grand Street) was the keystone for the Delancey grid; Love Lane (approximating the future East Broadway) would set the pattern of the Rutgers grid. The short road coming off the Bowery at Chatham Square, Division Street, was the boundary agreed to in 1765 (and still exists as a street today).

Here are Grand Street and East Broadway today—the two main roads of the 1700s. The three bridges in the image, from bottom to top, are: the Brooklyn, Manhattan and Williamsburg Bridges.

Let’s look at all three grids, including the city’s main grid. All three have the same working logic: make the best possible use of land to coordinate direct routes from the shore to the main roads. Delancey had extensive frontage on the Bowery, and his “cross streets” come off the curved Bowery at near right angles and lead directly to the shore. Rutgers, however, had extensive shoreline frontage along Cherry Street, and his property just barely touched the Bowery. His streets come up from shore and head to where his property accessed the Bowery.

The Commissioner’s Plan of 1811, which begins the main grid of the city at Houston Street (the small wedge at the top), is at a slight tilt to the Delancey grid, but actually uses the same logic. The city’s cross streets connect river-to-river, and each block is wide enough to accommodate two wharves, on either side of a street. Avenues are closer together at the shore than they are in the middle of the island. The city anticipated lots of cross town traffic, and movement of goods inland, from shore, and then up and down wide avenues.

Here it is without paint. I zoomed out because the grids are so distinctive you can still see them clearly from so far away, and it also gives an appreciation for just how large the area is.

The Rutgers and Delanceys weren’t just literally on opposite sides of the fence. During the Revolution, the Delanceys were staunch loyalists, while Henry Rutgers hosted meetings for the Sons of Liberty on his farm. (And in still another great moment in history, the father and grandfather of James de Lancey and Henry Rutgers were on different sides of the seditious-libel trial of Peter Zenger

Both families had long histories in New York. Stephen de Lancey came to New York in 1685, after Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes (which had been issued by Henry IV of France in 1598 to give some protections to the Protestants (Huguenots) after thousands had been slaughtered in the Saint Bartholomew’s Day Massacre of 1572. It’s amazing when you can go back so far—to think we have Delancey Street because of medieval religious wars!)

Anyway, Huguenots (and Stephen de Lancey was one) no longer felt safe in France and many came here; New Rochelle was a result of this migration. Stephen married into the van Cortlandt family (today’s park namesake), and his home was the original Fraunces Tavern, where Washington gave his historic farewell address to his generals (the building there now is a reproduction, it's faithful to the period architecture, but not the original building). Stephen’s son, Lieutenant Governor James de Lancey, was New York’s Supreme Court Justice under the British. His son, also James, “gridded” and leased out the property on the Lower East Side. Delancey had loose standards and leased out his land to artisans and craftsmen as well as to investors who turned around and sublet. But Delancey would be a Lower East Side landlord for a very short time before the Revolution. After the revolution, he lost his land and the Delancey clan, along with a boatload of other Tories, were re-located by the British to New Brunswick (Canada, not New Jersey; but in another weird coincidence that's where Rutgers

A law passed by the legislature of New York on May 19, 1784, provided for the speedy sale of confiscated and forfeited estates, and under it many sales were effected. The large city estate of James De Lancey, lying in the district bounded by the Bowery, Rivington Street, Division Street, and the East River, was sold, and De Lancey himself was attainted.A mix bag of folks bought up the Delancey properties, but fully half were purchased by New York’s rich established families, and many of the artisans had to move out, unable to afford the higher rents imposed.

Harmanus Rutgers (and his brother Anthony, from the previous post referred to above) were descendents of a wealthy brewing family that had come to New Amsterdam in 1636. Originally to Ft. Orange (Albany), they moved to New York in 1690. Harmanus (Henry’s grandfather) purchased 56 acres of Lower East Side land around 1728, and the original farmhouse was just off the Bowery. In 1751 a larger mansion was built farther in on the property, closer to the East River. Harmanus’s son, also named Henry, inherited the LES land in 1753. He was the father of the Revolutionary War Colonel, and namesake of Rutgers University. And while Henry Rutgers (Jr.) was a great philanthropist, when Queen’s College was renamed for him in 1825 the Board of Trustees was probably hoping for a larger bequeath than the $5,000 he left the school when he died in 1830. He had no children and his nephew, William Crosby, inherited the bulk of the estate.

Unlike James de Lancey, Rutgers preferred long-term leases and he let his land with “restrictive covenants” that required buildings of more substantial material than what was allowed to be built on the Delancey grounds. In effect, Rutgers exercised his own zoning.

From the Rutgers University Libraries:

An important method of controlling development was to require compliance with specified conditions. In May 1826, for example, Rutgers leased a lot to the mason Thompson Price. The lease stipulated that Price "build and erect a good substantial and workmanlike brick dwelling house not less than forty feet in depth, and not less than two stories in height, on the front of the said … premises, and so as to cover the whole front; but at no period of the term … shall there be more than one dwelling house." He also required his permission for leaseholders to sell their leases and reserved to himself first option to buy. Thus Rutgers was not only complying with state law regarding use of building materials that guarded against the ever-present danger from fire, he also maintained control over density of development and related quality-of-life issues. Uncontrolled development resulted in situations such as that at Corlears Hook, an impoverished neighborhood where in 1819 one building reportedly housed 103 people.

Rutgers Street, today running north-south mid-way through the grid, was the division between more substantial brick buildings (to the east side), and a mix of wooden and brick structures (to the west side); Cherry Street was the boundary between homes and stores, along the shore. Rutgers attracted a more stately class of tenants, including merchants, professionals, and those related to the shipbuilding industry, in addition to the artisans and craftsmen who sublet from the many owners of the (now former) Delancey properties.

Here’s the Ratzen Plan, 1766, before much was built, showing the farmland much more accurately than the Montresor map. The Delancey farm actually had an irregular northern boundary. The next map zoom’s in…

The Delancey Streets were already laid out by 1766 with a great central square. The “mansion plot” had previously belonged to freed slaves, Anthony Congo and Bastiaen in 1647, granted to them by Director-General Kieft of the Dutch West India Company (the city leader was as much a CEO as a politician). There will be more about this dastardly Director in the final post.

Orchard and Grand Streets retain their names today and originally were interrupted, ending in the middle of the sides of the square. It’s possible there was an orchard in the “Great Square,” but looking at the map it seems more likely that Orchard Street was named for the orchard on the mansion plot, from which the street extends south. Another colonial judge, Thomas Jones, had an estate on the hilltop of Mount Pitt (aka Jones Hill). We’ll look for his house in the third post of this series. You can see Rutgers original house near the Bowery, and the one that was constructed later, closer to Corlears Hook. We’ll also go looking for these in the third post.

From Lamb’s History of the City New York, showing the Delancey estate at the time of the Revolution. The northern boundary of the property did not neatly follow a future street. What’s most ironic is the open space. The Great Square (or Delancey’s Square on this map) is about the most tenement-congested four-square-block area on the Lower East Side today, and is now surrounded by much open space and parks where tenements have been torn down.

The first map below shows the north-south streets (and they’re pretty close to the compass orientation). In blue, Delancey’s original names for the streets are shown first (when applicable), some retained their original names. Two roads (Allen and Ludlow) were added later, shown in black, and crossed through the square on either side of Orchard Street.

A nifty way to remember the streets is to use the actual square, and history itself! First, visualize the square and remember that Grand and Orchard Street cross in the middle. Between the Bowery and the western edge of the square Delancey laid out three streets: First, Second and Third. In 1817 they were re-named for heroes from the War of 1812: Chrystie, Forsythe and Eldridge, in that order. To remember the order, think “CaFE.” (It is the Lower East Side after all.) The streets on the opposite side of the square retain their original names: Essex, Norfolk and Suffolk—all English counties, and in alphabetical order. The two roads that were later laid out on either side of Orchard Street, Allen and Ludlow (also war of 1812 heroes), both have two Ls in their names—they came Later. There are many more streets after Suffolk, in fact Arundel (another English county), was renamed Clinton. But if you’re going out on the Lower East Side, you’re likely going to one of those streets.

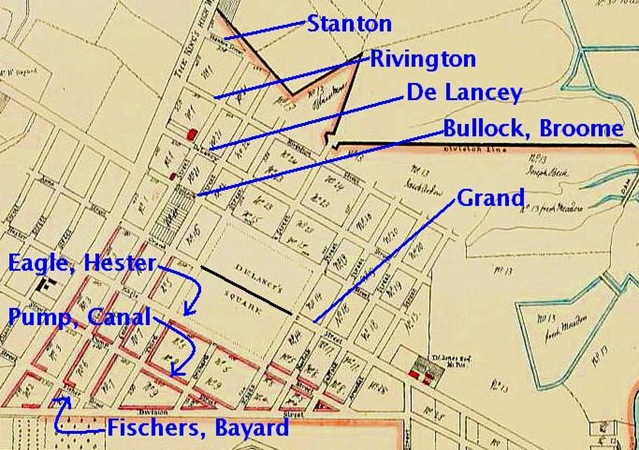

I don’t have a trick for remembering the east-west streets. The lower square’s road was originally named Eagle Street, and changed to Hester, the daughter of Jacob Leisler of Leisler Rebellion fame. Below Hester was Pump Street, eventually linked to and renamed Canal; and below that was Fischers Street, renamed Bayard. The top of the square was Bullock, renamed Broome Street (the first alderman after the British evacuation), followed by Delancey, Rivington (a publisher of a pro-British paper during the Revolution but secretly spying for George Washington), and Stanton (a foreman on the Delancey estate). There’s nothing consistent with the names of these streets to remember them, though they are in alphabetical order above Broome.

A very cool map from a great old book, A Tour Around New York, by Felix Oldboy of the area in 1782, during the Revolution, when the British had been occupying New York for six years! Delancey Square has gotten quite a work over and is now a defensive wall along the high ground of Grand Street. But General Charles Lee, a soon-to-be American, had spent months preparing New York’s defenses against the British before George Washington arrived so much of the wall may have already been in place by the time the British took control of New York.

We'll see the map again in another post but it's so cool I thought I'd show it here.

The 1820s were the apex for the social elite on the Lower East Side. We’d fought the “second Revolution” in the War of 1812, and with the opening of the Erie Canal in 1825, New York was on a road from which it would never look back. Beloved George Washington had passed away in 1799, but the Marquis de La Fayette, who helped win the Revolution and was nearly as much beloved as Wasington, returned to New York City in 1824 to one of the grandest receptions the city’s ever known. He was feted at Colonel Rutgers’ mansion when this part of town, along with the Battery and Bond Street, was among the most genteel of high society. The Mount Pitt Circus operated at Grand Street and East Broadway from 1826-1829. Corlears Hook, nonetheless, remained a raunchy, overpopulated red light area. Unlike today, back then you could almost throw a rock from where the wealthiest and poorest people lived.

The commercial center was still in lower Manhattan on Pearl Street, and the movement of progress was initially not up Broadway, but up the Bowery. Brooks Brothers opened at the corner of Cherry and Catherine Streets in 1818…

And in 1826 Lord and Taylor opened their first store at 47 Catherine Street. The picture below was obviously taken long after that; Lord and Taylor continued to occupy their buildings even after opening additional branches uptown, and they stayed at this location until 1866. The signs out front say “selling off.” The “department store” didn’t exist in the early 1800s, and they were “dry goods” stores, or sometimes called a “store and loft.” Brooks Brothers was probably a combination dry-goods store and tailor.

Here’s what Valentine’s Manual of Old New York, 1921 says about Lord and Taylor and Catherine Street, circa 1820s…

Further development would take place in the vicinity of the Bowery, a part of town on the upswing. In 1825, the Bull’s Head Tavern, located where the Manhattan Bridge meets Canal Street today (and a 5-minute walk from the Catherine Street location above) was still part of the cattle market whose tanners and butchers had so polluted the Collect Pond since the 1700s, now filled in for about 10 years. Now the area was changing. Of the Bull’s Head Tavern, Gotham says,

Some of [their] customers, bolstered by gentry families filtering in from the lower wards, wanted to transform the Bowery into a more genteel neighborhood. taking aim at the stink, the endless whinnying, lowing and grunting, and the occasional steer running amok and goring passers-by, they set about driving the Bull’s Head from the area. In the mid-1820s, an association of socially prominent businessmen bought out Henry Astor [John Jacob’s brother] and dismantled his enterprise….[I]n place of the old tavern, the consortium set about erecting Ithiel Town’s splendid Greek Revival playhouse—the New York (soon to be Bowery) Theater.

(added 3/6/2011)

The above image was a later version of the Bowery Theater. Ithiel Town's Bowery Theater, originally called the New York Theater, looked like this...

Here are those locations today: (1) Brooks Brothers, 1818; (2) Lord & Taylor, 1826; (3) the Bowery Theater, 1826; and (4) Rutgers’ mansion where he received Lafayette in 1824.

Below are West Broadway, Broadway, and East Broadway. West Broadway was named in 1899, and a popular explanation for its name was to trick people into using an alternate route other than the very congested Broadway. The same logic is often used to describe the origin of East Broadway. But East Broadway was named in 1831, and besides the fact there is no way that that route could have served as an alternate to Broadway, in the early 1800s it was an east Broadway, which then barely extended past today’s City Hall. Throughout most of the 1800s, both streets were popular commercial centers. Along with Grand Street they were, in fact, the original “Ladies Mile,” the name of the historic shopping district stretching from 14th to 23rd Streets, between Fifth and 6th Avenues.

History often paints immigration in broad strokes: the Irish came with the potato famines of 1845-1849; the Germans came after the Central European revolutions in 1848; the Chinese came at the end of the Gold Rush and the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad, after rampant discrimination out west in the 1870s; the Italians came following natural disasters and economic depression in southern Italy in the 1870s; and the Russian, Polish and Eastern Europeans, mostly Jewish, came as a result of pogroms and rampant discrimination starting in the 1880s. All true; but one might think New York had little immigration until the mid-1840s.

Between 1820 and 1840, the population of Manhattan grew from 123,000 to over 310,000. Mostly English, German (including German Jews) and Irish came to the new country for their own reasons, poverty being the most common. Two things would bring the Irish in huge numbers before the potato famines. They were a huge part of the labor force that built the Erie Canal between 1817 and when it opened in 1825. Also in 1817, the Black Ball Line began running packet ships between Liverpool and New York. What was different and significant about this operation was that they sailed on a regular schedule, no longer waiting for a full load before disembarking, and in “Priceline fashion,” it would’ve been better to fill a spot at a reduced fare than have no fare at all.

Many Germans who fought as mercenaries on behalf of the British stayed on after the Revolution, and some were joined by family (this was how John Jacob Astor came to New York, following his brother Henry who, according to Kenneth Dunshee's As You Pass By, came over as a Hessian soldier).

The Russian, Polish and Eastern European Jewish history with which the Lower East Side is closely associated is in some respects an easier history to wrap one’s mind around than the immigrant history that immediately preceded the area. The period from the 1880s until 1924 (when the wall on immigration went up) has its unifying threads of a people in similar situations, beliefs and on trajectories through history. Understanding the area between the 1840s and 1880s, however, can be like trying to unstir a cup of coffee.

Immigration had changed the area drastically when the following article was written for the New York Times in 1872—ten years before the waves of immigration that would come to define the area today. Titled: Old Houses: The Mansion of Hendrick Rutgers

Notice the author doesn't complain of Italians, they haven't arrived yet. And the Jews the author talks about are mostly German Jews, not yet the Russian, Polish and Eastern European Jews who are not due for another 10 years. In 1872 there are some Chinese nearby, on the other side of the Bowery but, like the Irish, they will for the most part be dispersed throughout the city in jobs as domestic servants. By the mid 1850s Kleindeutschland would take root with German-Jewish shops along Chrystie, Forsythe and Eldridge Streets, from Division to Grand. Germans, Hungarians and others would group together by language and culture (basically, city of origin). The author of the above article is in part describing original Kleindeutschland, which will simultaneously shift uptown and expand, transforming Avenue B into a German Broadway, and settling Yorkville further uptown by reach of the elevated train, as it's displaced by the masses arriving from Russia, Poland and Eastern Europe.

As the crescendo of immigration rises, Lord and Taylor, not knowing its breadth of depth, opens a branch store at Grand and Chrystie in 1853 (and remains open until 1902). As early as 1860 though, they sense the changes, and not so much a reaction to immigration as an awareness that Broadway is now “the place to be,” they open another branch at the corner of Broadway on Grand Street, nine blocks west. Brooks Brothers would move directly to Broadway and Grand in 1857.

The E. S. Ridley Department Store building survives today on Grand Street and Orchard Street, right in the middle of Delancey’s old square and in the midst of blocks choked with tenements. Ridley opened 1849, just before the German “wave.” In 1862, a horse drawn railroad line connected Grand Street with ferry terminals allowing shoppers from Brooklyn to easily shop Grand Street, creating an east-west shopping district that was Broadway’s closest rival. Ridley’s expanded to take up the entire block in 1883, just at the start of Eastern European and Russian “waves.”

Between the 1880s and 1920s, Italian and Eastern European immigration had the effect of turning previous immigrations almost into historical footnotes. Ridley’s would leave in 1901, followed by Lord and Taylor in 1902. (though thier flagship store had moved on long before). “By 1894,” according to Gerard Wolfe, “the population reached an astonishing 986 people per acre—one-and-a-half times that of Bombay, India!”

From Valentines Manual of Old New York, 1921, speaking about East Broadway from the 1850s up to the 1880s...

What’s incredible is how an area that saw so much change so quickly, can re-double the amount of change and in half the time. But that’s the story of New York.

The single most salient fact that illuminates the Lower East Side's most important role in history as an incubator for so many immigrant groups is that four world-renowned, multimillion-dollar, global, ethnic self-help groups started within a 5-10 minute walk of one another (though technically some are across the border from the area under discussion, and the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association started in San Francisco the year before.)