(Just before posting this, I read about Lara Logan with CBS. I still stand by those opening words; she was rescued by a group of women and soldiers within the same crowd. I’d like to think it was an aberration, but she was surrounded by a group of 200. It makes me think of Kitty Genovese. How much more backwards can a situation be when there’s civility in revolution and such barbarism towards an individual. And as for the press that thought it important to mention it, it doesn’t matter whether or not she was Jewish. The rest of this post will continue as originally written.)

There’s actually a great precedent for democratic ideals emblazoned in the Manhattan streetscape. The first great architectural wave to sweep the city (and the nation) was the 1830s and 40s Greek Revival movement, a building trend that went into frenzy mode after the Greek War of Independence and that country’s break from the Ottoman Empire in the 1820s. The city embraced the temple form in every building type from churches and commercial buildings to homes. So prolific was the style that you can’t walk a few blocks below 14th Street today without passing at least a few examples. Some of the more well-known include: Federal Hall National Memorial on Wall Street, Washington Square’s “The Row,” St. Peter’s Church on Barclay Street, and the Merchant’s House Museum—all adorned with entrance elements of columns and pediments that herald the birthplace of democracy. Let’s hope Egyptian architecture can one day evoke those ideals for a modern time.

About the same time as the Greek Revival movement, a smaller wave of Egyptian Revival architecture rippled across the nation following Napoleon’s (most undemocratic) conquest of Egypt, and then Britain’s likewise incursion down the Nile in the late 1700s. Publications from Napoleon’s expedition in the early 1800s (he took scientists with him) would fuel interest in Egyptian styles.

Chapters on Egyptian architecture in architecture books, when they are there, are usually the smallest—but they’re always the first. The truth is, in a way all architecture is Egyptian. Owen Jones says this in his seminal work on architectural ornamentation across the world’s great cultures, in The Grammar of Ornament (p. 47).

…[Regarding Egypt,] whilst we can trace in direct succession the Greek, the Roman, the Byzantine, with its offshoots, the Arabian, the Moresque and the Gothic, from this great parent, we must believe the architecture of Egypt to be a pure original style, which arose with civilization in Central Africa, passed through countless ages, to the culminating point of perfection and the state of decline in which we see it…The Egyptians are inferior only to themselves. In all other styles we can trace a rapid ascent from infancy, founded on some bygone style, to a culminating point of perfection, when the foreign influence was modified or discarded, to a period of slow, lingering decline, feeding on its own elements. In the Egyptian we have no traces of infancy or of any foreign influence; and we must, therefore, believe that they went for inspiration direct from nature.And Egyptian art almost received a prominent Fifth Avenue display alongside other great traditions. Have you ever noticed that the front of the Metropolitan Museum of Art appears to be missing something? It is. Richard Morris Hunt died in 1895 before his plans for the facade could be fulfilled. In Shaping the City (p. 10), Gregory Gilmartin explains,

The Fifth Avenue facade was dominated by four pairs of immense columns, and these were meant to serve as the pedestals for sculptural groups representing the ‘four great periods of art’: Egyptian, Greek, Renaissance and Modern. Between each pair of columns sat a niche where Hunt intended to set a copy of one great work from each historical era.It was “Modern” art that stuck in the craw of the trustees; who knew if it would stand the test of time, and so the niches remain blank today.

When we think of Egyptian forms, it’s the pyramid that first comes to mind—the tombs of the pharaoh. And many building tops around the city allude to it, some more obvious than others.

The step-pyramid atop the Bankers Trust Company Building (Trowbridge & Livingston, 1912) on Wall Street is one of the most hidden crowns in the city—not tall enough to be seen over surrounding buildings on the narrow streets of the Financial District. Here it is from three blocks away, between the steeple of Trinity Church (Upjohn, 1846) and 40 Wall Street (Severance, 1929), another pyramid-topped building.

The New York Museum of Jewish Heritage (Kevin Roche, 1996) is a postmodern hexagonal step pyramid. Appropriate for a museum that is laid out as a timeline of Jewish culture and history.

Courtesy of NYPI.net

Another form closely associated with the Egyptian is the Obelisk, built to flank the entrance of Egyptian temples. Central Park has the oldest manmade structure in the entire city, a tad over 3,600 years—Cleopatra’s Needle. According to the plaque on the monument, this one spent 1,588 years in Heliopolis, and 1,893 years in Alexandria (the Romans moved it there). On February 22, 2011, it will have spent 130 years in Central Park. Not until 5363 will Cleopatra's Needle have been in New York longer than Egypt—to put it in high mental relief, doubling the time since the year 0 only takes us to 4022!

Another obelisk stands in Madison Square, the Worth Monument (Batterson, 1857). Entombed beneath where Broadway crosses Fifth Avenue is General William Jenkins Worth, for whom Worth Street in lower Manhattan, and Ft. Worth, Texas are both named. He is a little remembered veteran and once great hero of the Mexican-American War of 1849.

Egyptian architecture lends itself to great bulwark structures that seek to impart a sense of mass, stability, strength and power. John Augustus Roebling, the genius architect of the Brooklyn Bridge, was originally inspired by an Egyptian design for the bridge towers. These were his 1857 plans…

From The Great Bridge, by David McCullough. Rensselear Polytechnic Institute.

Before looking at buildings around the city, let’s look at a few of the forms and features that distinguish Egyptian architecture, using the Temple of Dendur at the Metropolitan Museum of Art as a model. The temple is from 15 B.C., given to the Met in 1967.

Battered (or tapered) walls. They’re called “pylons” when two flank the entrance to a temple…

Narrow doors and windows…

A quarter-round, concave roof line, called a cavetto cornice…

Here are cavetto cornices on IS 90 at Jumel Pace and 168th Street (Dattner & Associates, 1999).

Two long gone structures, and substantial examples of Egyptian architecture, were the Croton Aqueduct’s 25 million gallon Distributing Reservoir, on the site of today’s New York Public Library, and the original “tombs” prison.

A most appropriate architectural mode for its function—the Nile was life for the Egyptians, and the reservoir made life possible in New York City. It stood from 1842-1900.

The New York Public Library

The New York Public LibraryThis view is looking north on Fifth Avenue from 40th Street.

The New York Public Library

The New York Public LibraryBattered walls…

The New York Public Library

Cavetto cornices…

The New York Public Library

The New York Public LibraryNarrow openings. This fantastic illustration from 1850 looks from about 6th Avenue towards the future site of Bryant Park, and the back of the NYPL. The lady and two children are crossing south on 42nd Street.

The New York Public Library

The New York Public LibraryHere’s about that spot today. The reservoir was where the NYPL is situated, somewhat obscured by trees of Bryant Park.

The reservoir might have been inspired by an earlier one, built by the Manhattan Company (the future Chase Bank) on Chambers Street between Broadway and Centre Street. The Manhattan Company was a much better bank than a water provider.

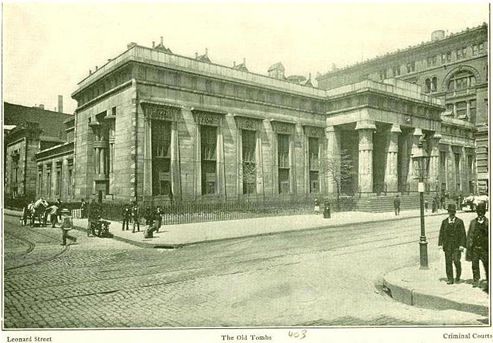

Albeit an unfortunate one, the “tombs” was another example of New York’s foray into Egyptian Revival architecture. Built over the poorly filled in Collect Pond at Leonard and Centre Street. The New York Halls of Justice and House of Detention, as it was officially known, served as the dark, dank prison from 1838-1902. The Manhattan Detention Center stands on the site today overlooking Chinatown (Bernie Madoff was there for a stretch).

The New York Public Library

The New York Public LibraryHere’s a zoom-in of the battered side panels of the windows, mimicing pylons flanking an Egyptian temple.

And this is the Leonard Street entrance (above, to the left). Paying no attention to the unsettling image of the young boy escorted into prison by two officials (it was way back in 1887), a cavetto cornice can be seen above the battered door, and two bundled palm leaf columns flank the entrance.

The New York Public Library

The inscription below the illustration reads: "They saw the policemen lead Pinney into the Tombs prison."

Here is an original of the columns above, on display in the Metropolitan Museum. This one has five bands bundling the palms together.

Looking at buildings standing around the city today…the least “pure” example is The Bowling Green Offices building at 5-11 Broadway (W. & G Audsley, 1898). The style is called “Eclectic” for just this reason, it mixes Classical, Egyptian, Renaissance and probably a few other styles in its facade.

What’s most Egyptian are the battered walls framing the entrance, and its cavetto cornice.

An upper floor window has a palm leaf cavetto “cornice.”

A row of squat composite (mixed style) columns have Egyptian elements as well.

To the right is an example of an Egyptian capital from Owen Jones, The Ornament of Grammar. Aquatic plants emerge from bundled papyrus in the illustration.

The Egyptians often looked to two plants that grew in the Nile to embellish their jewelry, pottery, columns and buildings: the lotus flower and papyrus plant.

This vase is currently on display at The Met, titled: White cross-lined ware vase with plant designs, from circa 3900–3700 B.C.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1912

And while the lotus blossom would be used by many cultures in art and architecture, it was first used by the Egyptians.

Courtesy of Common Bread website

Courtesy of Common Bread websiteAgain from The Met's collection, titled: Double "Tell el-Jahudiyeh" Vase with Incised Lotus Flowers, probably manufactured in Egypt, circa 1700–1600 B.C., with a close up on the lotus.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1923

And another example from The Met, in bronze: Lotus attachment element, circa 1070–664 B.C.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Theodore M. Davis Collection, Bequest of Theodore M. Davis, 1915

When looking at representations of papyrus and lotus, I think it’s easiest to tell them apart by the tops of the plants; papyrus has a smooth curved top while the lotus has pointy petals. I think the main image on the left is papyrus, all the other plant images are lotuses.

At the Temple of Dendur, The Met gives a description of the entrance: “Lining the temple base are carvings of papyrus and lotus plants that seem to grow from water, symbolized by figures of the Nile god Hapy….

… The two columns on the porch rise toward the sky like tall bundles of papyrus stalks with lotus blossoms bound with them…

…Above the gate and temple entrance are images of the sun disk flanked by the outspread wings of Horus, the sky god.”

Here’s a close up of the capitals, bundled papyrus stalks and lotus blossoms.

Though lotus blossoms are the main forms in the column’s capital, the carvings look to be papyrus.

A second Egyptian Revival came on the scene during the Art Deco movement, after the 1922 discovery of Tutenkhamen's tomb. The Chrysler Building’s elevator doors appear to be an Art Deco lotus-papyrus composite…

The Fred. F. French building (1927) on the east side of Fifth Avenue at the corner of 45th Street, was the first tall building north of 42nd Street. Its style is Art Deco with ancient themes; and though not purely Egyptian, the ancient Assyrian and Babylonian references were influenced by the Egyptians—it’s among the most beautiful buildings in the city.

Looking north on Fifth Avenue a few blocks south of the building (just above 43rd Street), it’s easy to miss one of the most beautiful water tower encasements in the city. (see the arrow?)

The beehives are a common embellishment on commercial buildings (especially banks) throughout the city, symbolizing thrift and productivity—not Egyptian. But the central element is a take on the solar disk from the Temple of Dendur, associated with the Sun God Ra and Horus.

But unlike the Temple of Dendur, the wings don’t stretch out from the solar disk, and instead appear on two griffins. Like the lotus, griffins appear in many different cultures, but they can be seen in Egyptian art as early as 3300 B.C. They united the most powerful beast and most powerful bird: the lion and the falcon (or eagle).

The main entrance...

Focusing just on the Egyptian elements, the lotus and what may be lotus buds, are arranged just as on the Temple of Dendur.

It makes sense that the west side would have the two buildings most committed to an Egyptian-inspired program, and just two blocks from each other: the Pythian and the Alexandria.

This black and white image of the Pythian at 135 West 70th Street (Thomas Lamb, 1926) doesn’t do it justice, but it’s impossible to get a good shot from the street. The architect was noted for his many Broadway theaters. It’s over the top exuberant with Egyptian, Assyrian and Babylonian themes—and it's polychromatic (multi-colored), just as the Egyptians did it. (Windows were added to the front when it was converted to condos in 1982. Lady Gaga lived here for a while with her family.)

Courtesy of Office of Metropolitan History, John Marshall Mantel for the New York Times

Courtesy of Office of Metropolitan History, John Marshall Mantel for the New York Times

On the portico, the capitals are Assyrian.

A close up on details above…

Lotus blossoms in two stages of growth. The chevrons, or wavy lines, underneath the griffin represent the Nile waters.

Columns with palm capitals.

And if you think the blue painted columns are the architect’s whimsy, check this out…from the Met’s collection titled, Kohl Tube in the Shape of a Column with a Palm Leaf Capital, circa 1390–1352 B.C.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Edward S. Harkness Gift, 1926

And lotuses detail the column’s base.

Serpents flanking lotuses are in the shadow of a cavetto “cornice” (it’s not really a cornice since it’s only about 8 feet up).

Egyptian columns are generally smooth, and spaced closer together than Classical (Greek and Roman) columns. This narrow opening is a side door to the right of the main entrance.

More close-ups on details from the above image show…

Cavetto “cornice” containing the solar disk, flanked by two snakes, just as on the Temple of Dendur.

…lotuses...

…and what appear to be lotuses at the base of the columns, but maybe papyrus.

Even the small fence is in the program, representing the Nile…

In the lobby of the Pythian…Palm capital with bands.

Lotuses and serpents adorn the shaft. Bundled papyrus above them?

And here’s an upper floor detail invisible from street level.

And Pharaoh sits on an upper floor, looking downtown…

This Pharaoh sits on display in the Met.

The Alexandria at 201 West 72th Street (Frank Williams & Associates, 1991) is prominently sited on the corner of Broadway just south of the Ansonia and has many papyrus, palm and other Egyptian-inspired motifs in its facade. The water tower encasement has a stylized papyrus or palm motif. (This is the building John Gosselin moved into.)

Stylized lotus blossom and papyrus shoots serve as pilasters around the water tank and on the upper floors...

…as well as below…

And lastly, sometime in the not-to-distant future you’ll be able to see this pyramid-inspired design, planned for West 57th Street between 11th and 12th Avenues. The architect is Bjarke Ingels.

Percy Shelley’s Ozymandias is one of my favorite poems and most apt for the time. It’s about the power of Pharaoh, and in particular Ramses II. The message is that no matter how wide-reaching or how firm the Pharaoh’s grip, there is one thing that will always ensure an end to Pharaoh’s autocratic rule…time (and Twitter?).

I met a traveler from an antique land

Who said: Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed;

And on the pedestal these words appear:

“My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!”

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.